Jul 01, 2020

by Christopher Anderson

It’s summer and fire season is ramping up in California. But this season is poised to be unlike any other: COVID-19 will likely reshape wildfire response priorities across the state, alter the frequency and locations of ignitions too, and hot, dry, windy weather is forecast to increase fire danger statewide.

While the pandemic is a relatively new problem, driven primarily by one factor—the GOP’s failure to appropriately respond to a national health crisis—the patterns of fire frequency and fire danger are the culmination of a long history of land management and environmental change, driven by a complex series of anthropogenic and ecological forces.

Here I avoid discussing the effects of COVID-19—that’ll be a future post—and instead briefly reflect on the recent history of fire in California. This history informed the choices we made as we started to build a new forest monitoring system—the California Forest Observatory—to better understand the drivers of wildfire behavior across the state.

We designed the Forest Observatory to support data-driven forest management activities that mitigate wildfire risk and increase wildfire resilience—for both people and nature.

The State of Fire

California has experienced a dramatic increase in fire frequency over the last 50 years, culminating in a decade of catastrophic wildfires. Over 20,000 fires have been recorded in the past decade, following over 300,000 ignitions in that period. The majority of these were started by people—over 80% occurred near roadsides or utilities infrastructure.

People play a critical role in sparking ignitions. We’re now exposed to larger and more frequent wildfires as the wildland-urban interface has grown and housed more and more residents. This is in part due to a growing population. California is home to nearly 40 million people; twice the population in 1970.

To support this growth, roads and utilities have expanded, fragmenting the state’s ecosystems and increasing the reach of anthropogenic ignitions.

And despite the thousands of ignitions each year, over 95% of fires are suppressed by first responders. Yet the largest fires keep getting bigger each decade. Why are the fires that get out of control so catastrophic?

Fires and Forest Health

The largest wildfires often emerge following hot, dry & fast wind events.

The Rim Fire, one of the largest California wildfires of the last decade, was sparked by an illegal campfire in Stanislaus National Forest that burned hot and fast as sustained summer winds carried flames through crowded forests. The weather was so intense that firefighters had to wait for weather conditions to improve to extinguish it. But not before over 250,000 acres had burned at high severity. And the notorious Camp Fire—which devastated the community of Paradise—started during sustained winds of 25 to 30 miles per hour, with gusts recorded at over 45 miles per hour.

Dry weather is a dominant driver of wildfire behavior, but it’s certainly not the only one. These dry winds blow through dessicated ecosystems; the state’s vegetation has been stressed by multiple intersecting anthropogenic forces.

First, as people settled and suppressed wildfires in this fire-adapted landscape, trees grew relatively undisturbed. Tree density has increased by 30% in forests since 1930, yet the average tree diameter decreased by 19% over that same period.

This turnover from few large, resilient trees to many small trees with low biomass has altered some key ecological dynamics: densely-packed trees use lots of water, exacerbating drought stress, and they often act as ladder fuels that carry surface fires to the canopy.

Second, California began a severe drought in 2012 that continues today. This drought is unique in California’s history due to a combination of extremely high temperatures and low rainfall. Since then, over 100 million drought-stressed trees have died from pests and pathogens.

The legacy of fire suppression disrupted the natural cycle of fire, leading to the growth of dense, fuel-packed forests, which has been further stressed by a decade of drought. As hot and dry conditions are expected to persist longer under climate change, opportunities to manage forests to reduce wildfire risk are dwindling. Can we restore the past cycle of fire?

Supporting Risk-based Management

What does “at risk” mean? And who, or what, is at risk?

Risk is a complex term. We break it down into three components: hazard, exposure & value.

Wildfire hazards refer to vegetation fuels and the intensity at which they would burn in a wildfire. But no two hazards are the same—the effects of a fire deep in the forest are different from a fire burning through a community.

Exposure then refers to the resources affected by wildfires. 82 percent of all buildings destroyed due to wildfires are located in the wildland-urban interface, and 816 of the 3,103 fires over the past decade have crossed city boundaries.

Natural systems are also exposed. California is home to thousands of native species, including 6,500 total plant species. Many are vulnerable; 158 plant species and 89 animal species are now threatened or endangered, often due to habitat degradation. Regular, low-intensity fires often improve forest health, but fire suppression and catastrophic wildfires can have devastating effects on plant and animal communities.

In designing the California Forest Observatory we decided we would quantitatively map hazard and exposure patterns—but not value.

Value describes importance, worth & usefulness. Sometimes value is expressed in financial terms, but often it’s not—what is the safety of your home worth? Or the value of experiencing nature? We don’t attempt to estimate value—it’s not ours to assign.

A New Forest Monitoring Platform

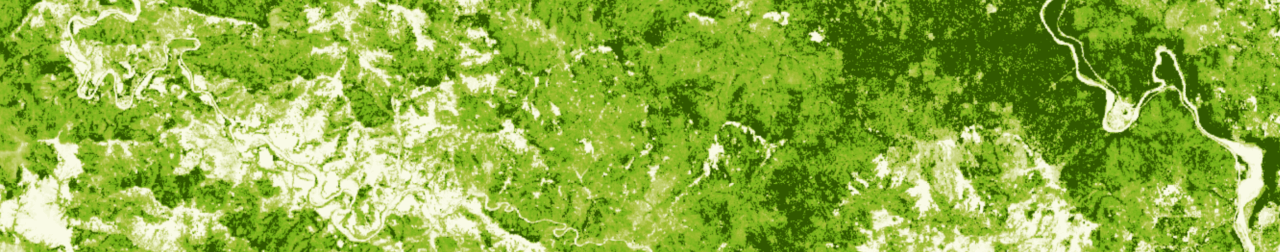

We designed the California Forest Observatory to map the complex patterns that drive wildfire behavior to provide unprecedented insights into the past, present & future of wildfire and forest health in California.

By combining satellite data, AI & ecological modeling, the Forest Observatory provides regularly updated, high resolution data on ignitions, fuels & the people, property and natural resources that are exposed to wildfires.

By providing these data for free to public institutions, universities & NGOs, we hope to develop data-driven land management strategies that increase wildfire resilience—for forests and communities—and enable people and nature to thrive together.

Check back for more updates soon. We plan to launch the Forest Observatory website in September 2020, and we’ll be posting all sorts of information: user guides, data descriptions, use cases & more.